Reading Playboy for the articles: March 1967

Orson Welles, Sharon Tate and a Fox River bachelor pad monument to MCM excess

My wife, Lisa, has acquired a large collection of vintage Playboy magazines. I'm flipping through those issues that catch my attention and offering my thoughts on the non-photographic content that filled its pages. You know, the articles.

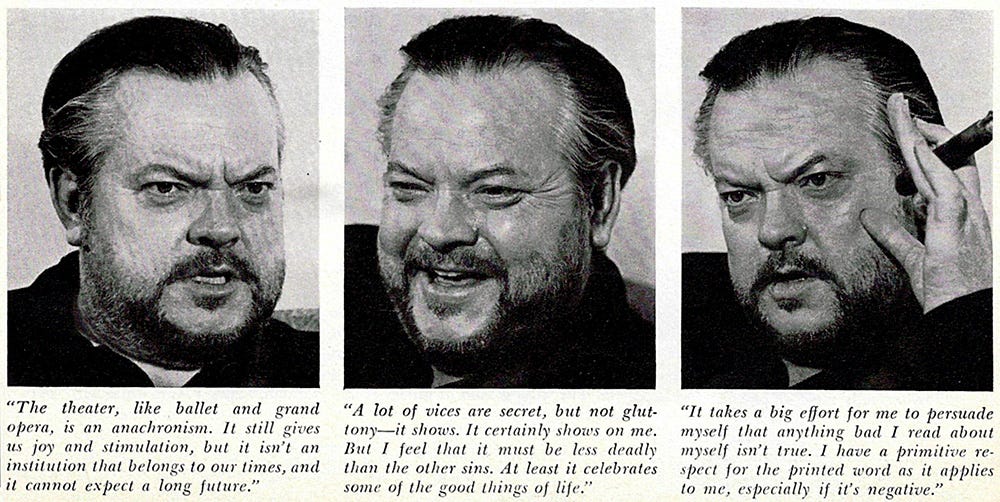

The Interview: Okay, I’ve come to accept that “Highlights” is a pretty useless category header when the obligatory interview fills that space every single time. So let’s just dispense with the pleasantries and accept that the interview will go here every time and dedicate a slot to it. And what a slot we have this go-round: The great Orson Welles, interviewed by Kenneth Tynan. I took my first notice of Welles when he was shilling for the Dark Tower game in the early 1980s and only later learned that he was a filmmaker who’d also sent the U.S. into a panic with his War of the Worlds radio broadcast. He was, suffice to say, an interesting character who is self-aware the way most celebrities aren’t.

PLAYBOY: Talking about critics, you once complained: “They don’t review my work, they review me.” Do you feel that’s still true?

WELLES: Yes—but I suppose I shouldn’t kick about it. I earn a good living and get a lot of work because of this ridiculous myth about me. But the price of it is that when I try to do something serious, something I care about, a great many critics don’t review that particular work, but me in general. They write their standard Welles piece. It’s either the good piece or the bad piece, but they’re both fairly standard.

PLAYBOY: In an era of increasing specialization, you’re expressed yourself in almost every artistic medium. Have you never wanted to specialize?

WELLES: No, I can’t imagine limiting myself. It’s a great shame that we live in an age of specialists, and I think we give them too much respect. I’ve known four or five great doctors in my life, and they have always told me that medicine is still in a primitive state and that they know hardly anything about it. I’ve known only one great cameraman—Gregg Toland, who photographed Citizen Kane. He said he could teach me everything about the camera in four hours—and he did. I don’t believe the specialist is all that our epoch cracks it up to be.

The conversation then shifts to Welle’s 1967 Falstaff film (retitled Chimes at Midnight after this interview was conducted). The film is based on five Shakespearean plays, condensed into a two-hour film.

PLAYBOY: Do you agree with W.H. Auden, who once likened him [Falstaff] to a Christ figure?

WELLES: I won’t argue with that, although my flesh always creeps when people use the world “Christ.” I think Falstaff is like a Christmas tree decorated with vices. The tree itself is total innocence and love. By contrast, the king is decorated only with kingliness. He’s a pure Machiavellian. And there’s something beady-eyed and self-regarding about his son—even when he reaches is apotheosis as Henry V.

PLAYBOY: Do you think Falstaff is likely to outrage Shakespeare lovers?

WELLES: Well, I’ve always edited Shakespeare, and my other Shakespearean films have suffered critically for just that reason. God knows what will happen with this one. In the case of Macbeth or Othello, I tried to make a single film into a filmscript. In Falstaff, I’ve taken five plays—Richard II, the two parts of Henry IV, Henry V and The Merry Wives of Windsor—and turned them into an entertainment lasting less than two hours. Naturally, I’m going to offend the kind of Shakespeare lover whose main concern is the sacredness of the text. But with people who are willing to concede that movies are a separate art form, I have some hopes of success. After all, when Verdi wrote Falstaff and Othello, nobody criticized him for radically changing Shakespeare. Larry Olivier has made fine Shakespearean movies that are essentially filmed Shakespearean plays. I use Shakespeare’s words and characters to make motion pictures. They are variations on his themes. In Falstaff, I’ve gone much further than ever before, but not willfully, not for the fun of chopping and dabbling. If you see the history plays night after night in the theater, you discover a continuing story about a delinquent prince who turns into a great military captain, a usurping king, and Falstaff, the prince’s spiritual father, who is a kind of secular saint. It finally culminates in the rejection of Falstaff by the prince. My film is entirely true to that story, although it sacrifices great parts of the plays from which the story is mined.

Later in the interview, the conversation turns to the theological.

PLAYBOY: Do you believe in God?

WELLS: My feelings on that subject are a constant interior dialog that I haven’t sufficiently resolved to be sure that I have anything worth communicating to people I don’t know. I may not be a believer, but I’m certainly religious. In a strange way, I even accept the divinity of Christ. The accumulation of faith creates its own veracity. It does this in a sort of Jungian sense, because it’s been made true in a way that’s almost as real as life. If you ask me whether the rabbi who was crucified was God, the answer is no. But the great, irresistible thing about the Judaeo-Christian idea is that man—no matter what his ancestry, no matter how close he is to any murderous ape—really is unique. If we are capable of unselfishly loving one another, we are absolutely alone, as a species, on this planet. There isn’t another animal that remotely resembles us. The notion of Christ’s divinity is a way of saying that. That’s why the myth is true. In the highest tragic sense, it dramatizes the idea that man in divine.

For those of you who are curious about such things, Welles also discusses his clairvoyance, the death of live theater and his opinions of various European and U.S. film directors in other parts of the interview. Fascinating through and through.

Highlights: This isn’t really a highlight, but the Bacardi ad amused me. For the curious, I looked up the Bacardi Party album the ad offers for a grand $1.25. It’s a compilation including such artists as Woody Herman, Ray Anthony, the Four Freshmen and Harry James. Not quite as hip as I was expecting but I may just grab one for novelty sake—they’re readily available from various online sites for an average of $2. Not a bad inflation rate over the past 50-plus years!

Okay, this next section is a bit awkward. I don’t normally comment on Playboy pictorials but this is different—a four-page spread featuring actress Sharon Tate (yes, that Sharon Tate) promoting one of three films she starred in that came out in 1967. This one is The Vampire Killers (later retitled The Fearless Vampire Killers) and the photographer for the spread is the film’s director, and Tate’s future husband, Roman Polanski. The film mixed comedy and horror with Tate’s easy sexuality to mixed results, but the leading role helped further Tate’s upward career trajectory. Shocking to realize she would be dead in two years, a murder victim of the Manson family.

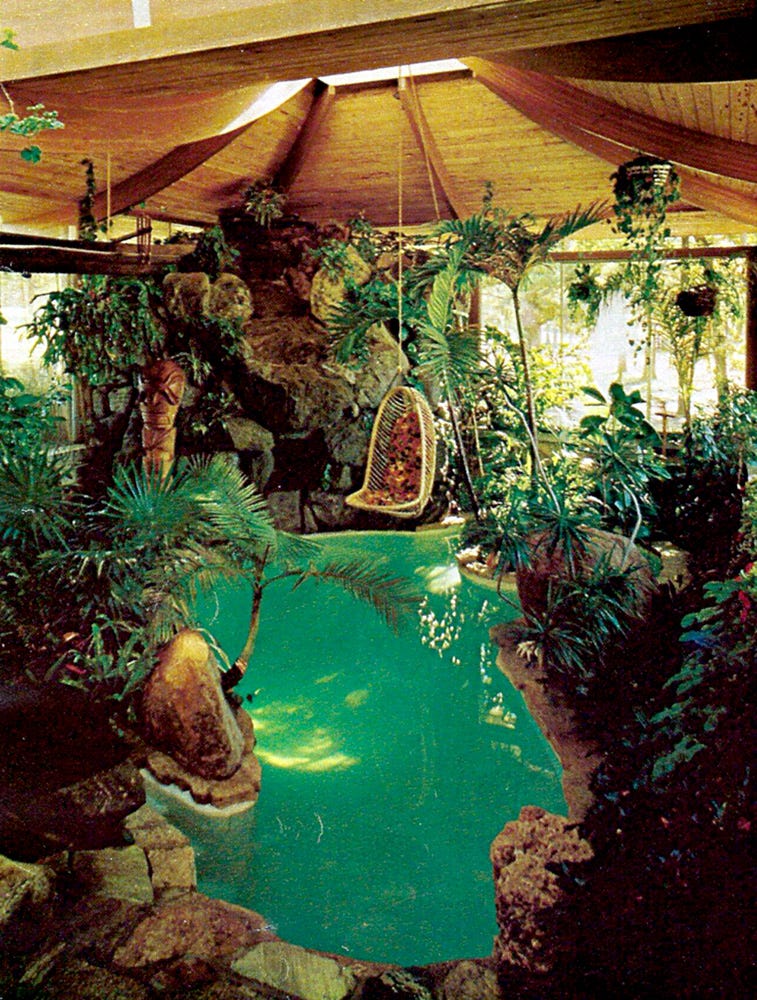

Holy moly! This house… this amazing house! Okay, granted, the mustard-yellow shag carpet is an unfortunate choice but everything else? This is a gonzo bonkers mid century exercise in extreme architecture. This place—which sadly does not have an official name—was built along the Fox River in McHenry County, Ill., just outside of Chicago, by Don Devine, a young executive with more money than sense. This enormous sprawling house has separate areas sheltered under several domed roofs, each topped with a skylight. The outside looks intriguing, but the inside is where things start to get wild.

Upon approaching the main entrance you know this isn’t a normal house—the only access is via stepping stones across a pool complete with the first of what will prove to be several waterfalls.

Inside, guests cross a bridge over another pool with a much larger waterfall, foxtail palms and soaring wooden ceilings. Groovy, man!

But it gets even better! An entire wing is devoted to an indoor pool filled with tropical palm trees, plants and a nice Marquesan-style tiki carving. There’s a cave hidden behind yet another waterfall that is adorned with animal skins draped across random boulders and a fully stocked bar. There was a massive kitchen. The lower level has a full-sized sauna. There are expansive common areas for hosting parties and plenty of bedrooms for guests to stay overnight. This place is amazing.

Alas, it may no longer exist. The only mention of it I’ve been able to find online outside of this Playboy article is a piece from the August 30, 1987 edition of the Chicago Tribune. The home had changed hands several times since the Playboy article and the current owner—and unnamed hotel executive—had knocked out most of the walls, junked the tikis and converted the place into a faux Japanese tea house that functioned as a quirky bed and breakfast. The executive shared in the piece he was about to give the property to his newly-married 22-year-old son, so presumably the B&B business was discontinued soon after. I’ve gone so far as to look at the Google Maps satellite view of McHenry County, scrolling along Fox River to try and spot the distinctive roof line, to no avail. The area has grown a lot over the past 30 years and I fear this amazing home has fallen victim to the wrecking ball to make way for a cookie-cutter subdivision. Lord knows this world needs more cookie cutters.

One article, an opinion piece by Paul Goodman, caught my attention. It posits the quaint notion that activist students are poised to be a political power for decades to come. The fact that Goodman envisions any coherence to these Baby Boomers’ political inclinations in the future is outright laughable half a century later. Here’s the opening paragraph to give you a taste:

Predictions about the future of America during the next generation are likely to be in one of two sharply contrasting moods. On the one hand, the orthodox liberals foresee a Great Society in which all will live in suburban comfort or the equivalent; given a Head Start and Job Training, Negroes will go to college like everybody else, will be splendidly employed and live in integrated neighborhoods; billboards will be 200 yards off new highways, and the arts will flourish in many Lincoln Centers. On the other hand, gloomy social critics, and orthodox conservatives, see that we are headed straight for 1984, when everyone’s life will be regimented from the cradle to the grave by the dictator in Washington; administrative double talk and Newspeak will be the only language; Negroes will be kept at bay by the police (according to the social critics) or will be the pampered shock troops of demagogs (according to the conservatives); we will all be serial numbers; civil liberties and independent enterprise will be no more.

I have to appreciate the not-so-subtle digs Goodman gets in on Lady Bird and Lyndon Johnson. Beyond that, there’s not much to see here as all of his keen insight sports a sell-by date of 1967.

One of my favorite things about these old magazines are the ads (had you guessed?). So many unexpected, out-of-left-field advertisements catch my attention, there’s no way I could share them all even if I were to devote myself to chronicling them. So I keep my powder dry, mostly. Take the ad below. Start by name-dropping Gauguin. That means it’s classy. Then pop the question: Two weeks in Tahiti for $585, including airfare? Yes, please! Ah, to be a well-to-do globetrotter back in the day. Say “Howdy” to Marlon Brando for me.

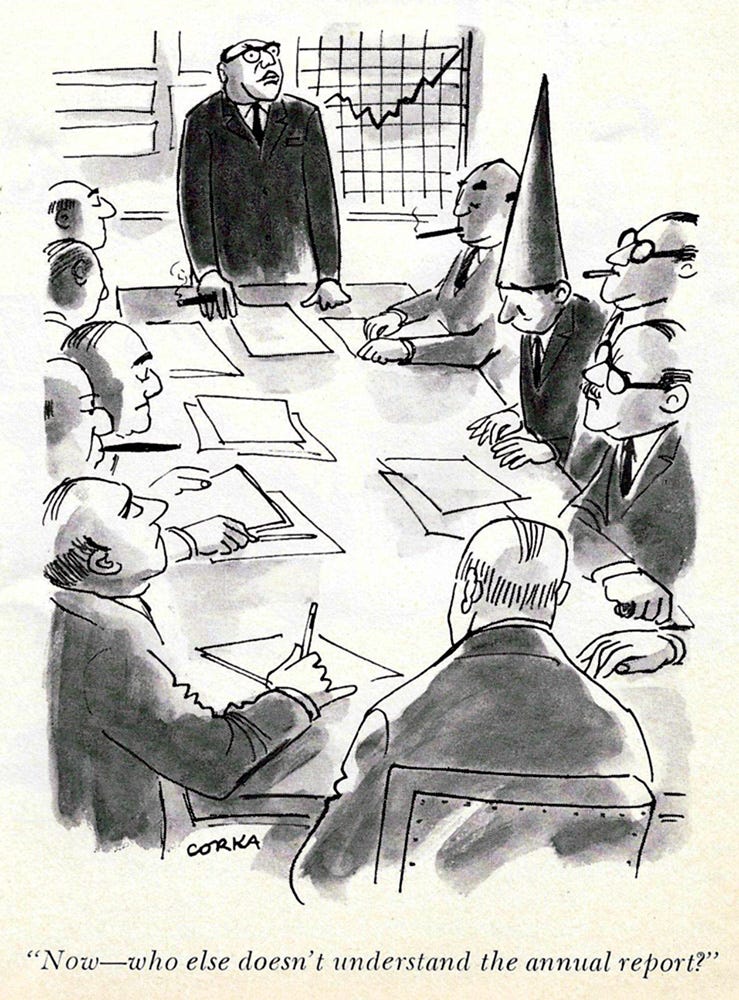

Finally, one of the famed Playboy cartoons, included here solely for the fact that it made me laugh.